- June 15, 2020

- COVID-19

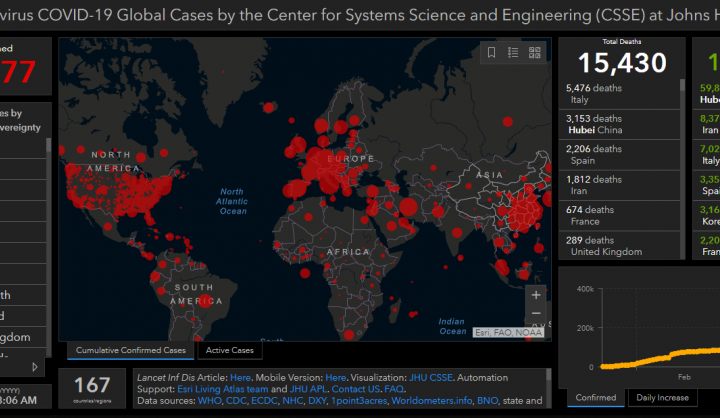

America is in the midst of a pandemic, but not all Americans are in the pandemic equally. While some people have called the virus “the great equalizer,” the concept of equal infection is false. Yes, the virus appears to infect whatever body it can. But thanks to historic and institutional racism, the virus is infecting and killing people of color at astonishingly high rates. COVID-19 can not be an equalizer when systemic oppression has spent centuries making people racially unequal.

The states and cities that are collecting infection data by race have shown a significant difference in positive COVID-19 cases and virus deaths between patients of color and white patients. Research by the Brookings Institute showed that people of color are vastly overrepresented in coronavirus infections and fatalities; “in Louisiana, Blacks represent about one-third of the state population but 70% of COVID-19 deaths. Most of these deaths are centered in the New Orleans area. Blacks in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, represent roughly 45% of diagnoses and over 70% of deaths related to COVID-19.”

While there are several different factors that contribute to the higher rates of death and infections among communities of color, major ones include redlining practices, environmental injustice, institutional prejudice and bias in healthcare. African-Americans, Latinxs, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives (AI/AN)* have particularly borne the brunt of these factors, with high rates of coronavirus comorbidities and limited access to running water for hand washing.

Unfortunately, many states and cities are not even tracking coronavirus cases by race, and with the limited tests available nationwide, the real numbers are probably much higher. In New York City and Illinois, two places that are tracking testing by race, white residents are more likely to get virus tests than Black residents, which again means that the actual toll on communities of color will be higher than we know right now. There is also emerging evidence that Hispanic populations are disproportionately affected by the virus. This is unacceptable; every public health department must be tracking anonymized data by race to appropriately identify and funnel resources to our most susceptible populations, who are in these vulnerable positions because of centuries of discriminatory policies.

In many of these communities, there is understandable suspicion around government collection of racial, especially when it concerns medical research. This “legacy of distrust” means that culturally-competent medical care and transparent data collection practices are paramount. To help spread the word in Indian Country, Johns Hopkins University is working with the Indian Health Service to adapt public service announcements for various tribes, and the Urban Indian Health Institute has produced a set of recommendations for best practices around AI/AN data collection. Various medical researchers are also compiling expert guidance on cultural perspectives and stigmatization.

Without thoughtfully-collected, anonymized racial data, we will not be able to flatten the curve of infections and provide critical care to those suffering the most, and we will continue to compound inequalities instead of using this moment to face them head on. This is the time for bold and courageous leadership, so we need leaders to meet this moment in history and address the current — and future — needs of unprotected racial groups before it is too late.

*In this article, the terms Native, Native American, and American Indian/Alaska Native are used interchangeably, in accordance with the Urban Indian Health Institute’s practices. These terms acknowledge the varying ways that North American Indigenous peoples must identify within the American racial structure and English language.