- January 12, 2017

- Public Health

City governments, especially along the U.S.’s Gulf Coast, have one more reason to worry about their vacant and abandoned housing stock: Zika.

Empty homes cost cities tax revenue, depress home prices, and contribute to housing shortages. They can attract squatters and increase crime and possibly even obesity.

And there’s reason to believe they can drive Zika virus outbreaks by harboring the mosquitos that transmit the disease. For this original analysis, I reviewed data from Miami, Florida, where the contiguous U.S.’s first locally-transmitted Zika outbreaks struck. I found that Zika took hold in neighborhoods already experiencing unusual rates of residential vacancy and concentrated poverty.

These factors might not only help explain Zika in Miami, but predict Zika risk in other warm-weather cities where Aedes aegypti mosquitos can thrive. With a few modifications, these cities could get ahead of Zika risk using the same playbook many have used to combat vacant properties in recent years.

An urban health risk

By now, Zika is a household name. Most people infected with Zika won’t have symptoms. Yet, pregnant women infected with Zika face a heightened risk of delivering a child with serious birth defects, including microcephaly. There’s no effective vaccine and 2018 is considered an ambitious deadline for developing one.

Major Zika outbreaks are ongoing in Puerto Rico and much of Latin America, and case counts are expected to grow in Asia. While 49 U.S. states have reported travel-related Zika cases, local transmission by infected mosquitos is the main worry for health officials.

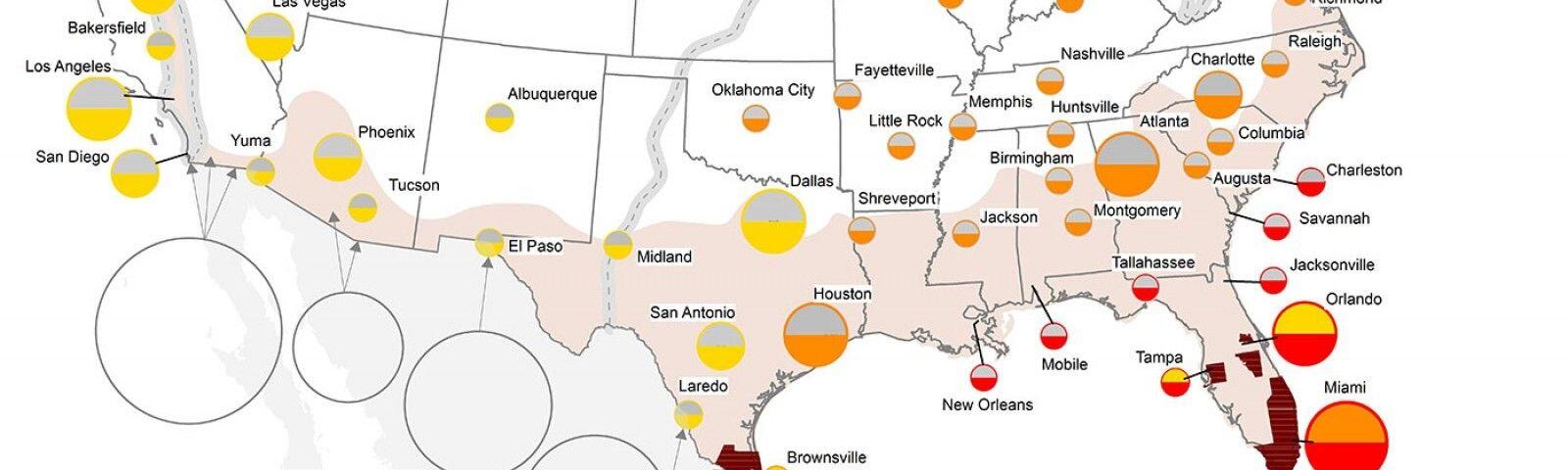

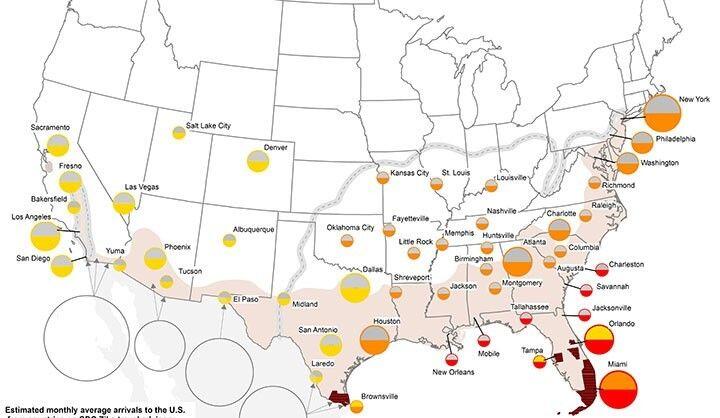

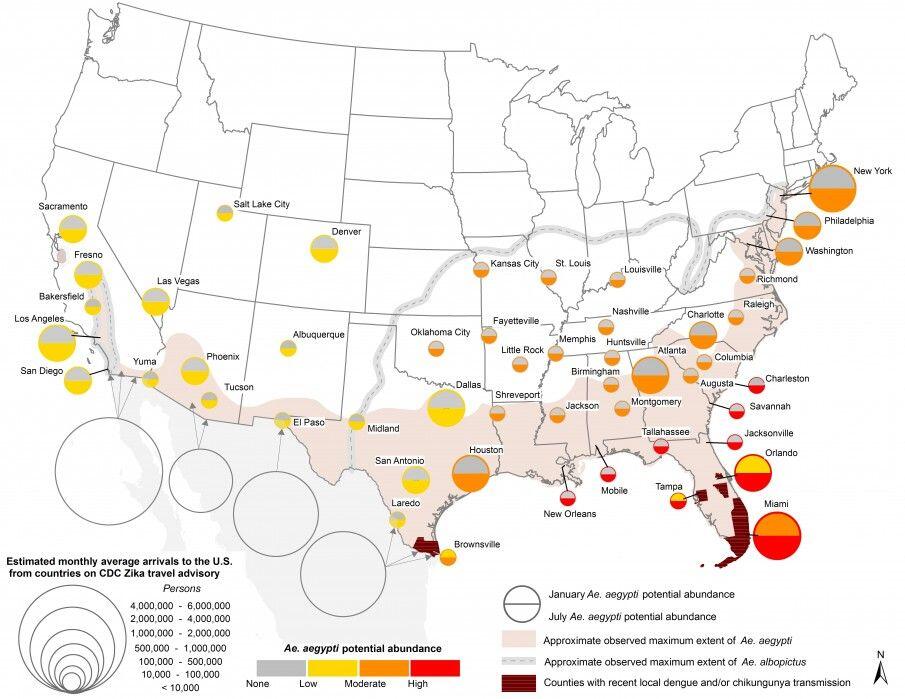

So far, the only identified cases of mosquito-borne transmission in the U.S. have happened in Miami, with another small cluster in the border city of Brownsville, Texas. But Aedes aegpyti, the mosquito responsible for most transmission, can be found in warm, wet climates throughout the American South, as far west as California, and as far up the Eastern Seaboard as New York City. Though cooler weather will limit risk in the winter months, CDC director Tom Frieden predicted that Zika will return annually. That scenario puts dozens of large U.S. cities at risk for Zika in 2017, as map below illustrates.

Controlling the Aedes aegypti mosquito is key to controlling risk. The mosquito breeds in standing water, often in manmade containers like gutters and discarded tires, and prefers feeding on humans. These traits attract Aedes aegypti to cities and demand a community-centered response: while aerial insecticide spraying may be necessary to halt a large-scale urban outbreak, “the only long-term solution” is sustained, community-based efforts to clean up potential breeding sites.

The bad news for city leaders is that these efforts are notoriously hard and mosquito control is often considered the responsibility of county and state officials. The good news is that Miami’s outbreaks may offer lessons to help other cities target their own programs.

Miami’s outbreaks: where and why

The first confirmed cases struck Miami in July. Epidemiologists descended on the trendy Wynwood district, just north of downtown. Then came Miami Beach, the beach resort city comprising barrier islands off of Miami’s eastern coast. Finally, a cluster of cases was detected around Little River, another residential neighborhood on the city’s north side. By December 9, all three had been cleared from “active transmission” status.

Miami Beach’s outbreak could be explained by the high density of travelers coming from Zika-affected countries, the daytime exposure of people sunbathing, and the difficulty of mosquito control around high-rise buildings. But why Wynwood and Little River? And what do these outbreaks tell us about neighborhood Zika risk?

Wynwood, sometimes called “Little San Juan” for its large Puerto Rican community, has been rapidly gentrifying over the past ten years. Artists have transformed the exteriors of many of the area’s large industrial buildings, including the Wynwood Walls, which has driven a hipster feel and growing fashion scene in the neighborhood’s commercial areas.

But, as the New York Times reported, while parts are bustling and visually appealing, Wynwood includes a “still-tattered section of run-down buildings where residents struggle in poverty.”

I looked at data from the U.S. Census and the U.S. Postal Service to assess whether Zika in Wynwood and Little River had anything to do with those run-down buildings and resident poverty. I found strong links.

First, I looked at residential vacancy. Vacant and foreclosed homes have been identified as major potential breeding sites for mosquitos: as Sonia Shah wrote for the Washington Post, swimming pools in foreclosed homes were implicated in Florida’s 2009 dengue outbreak and Bakersfield, California’s 2007 West Nile virus outbreak.

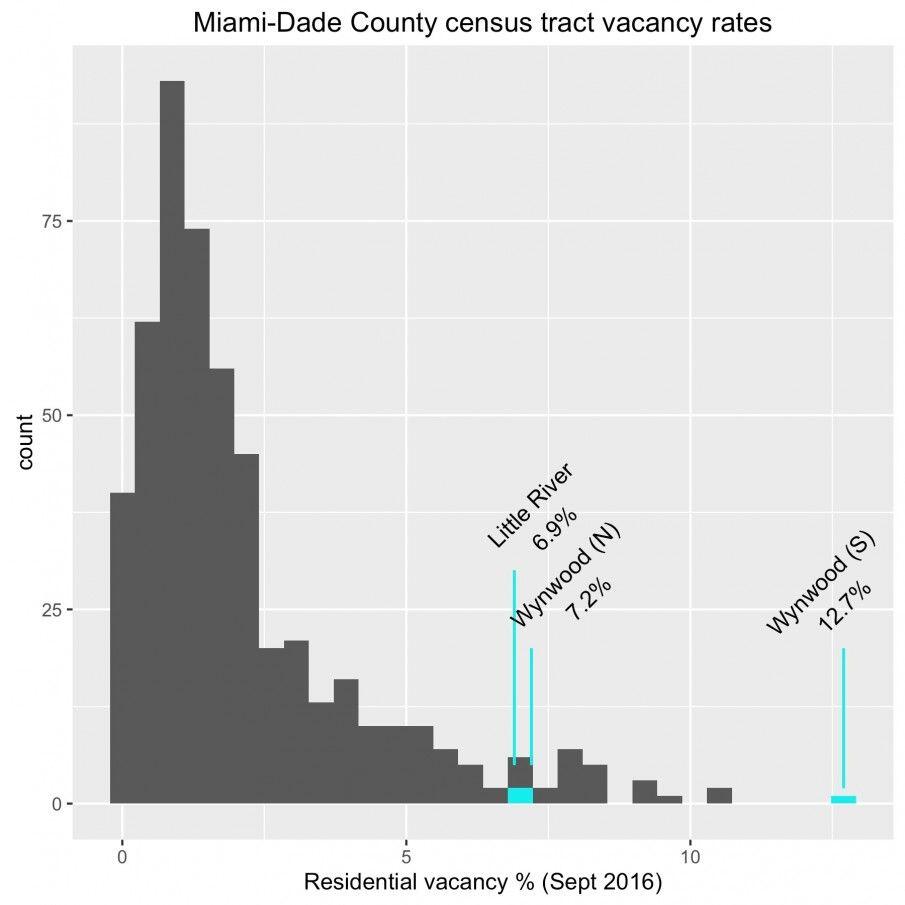

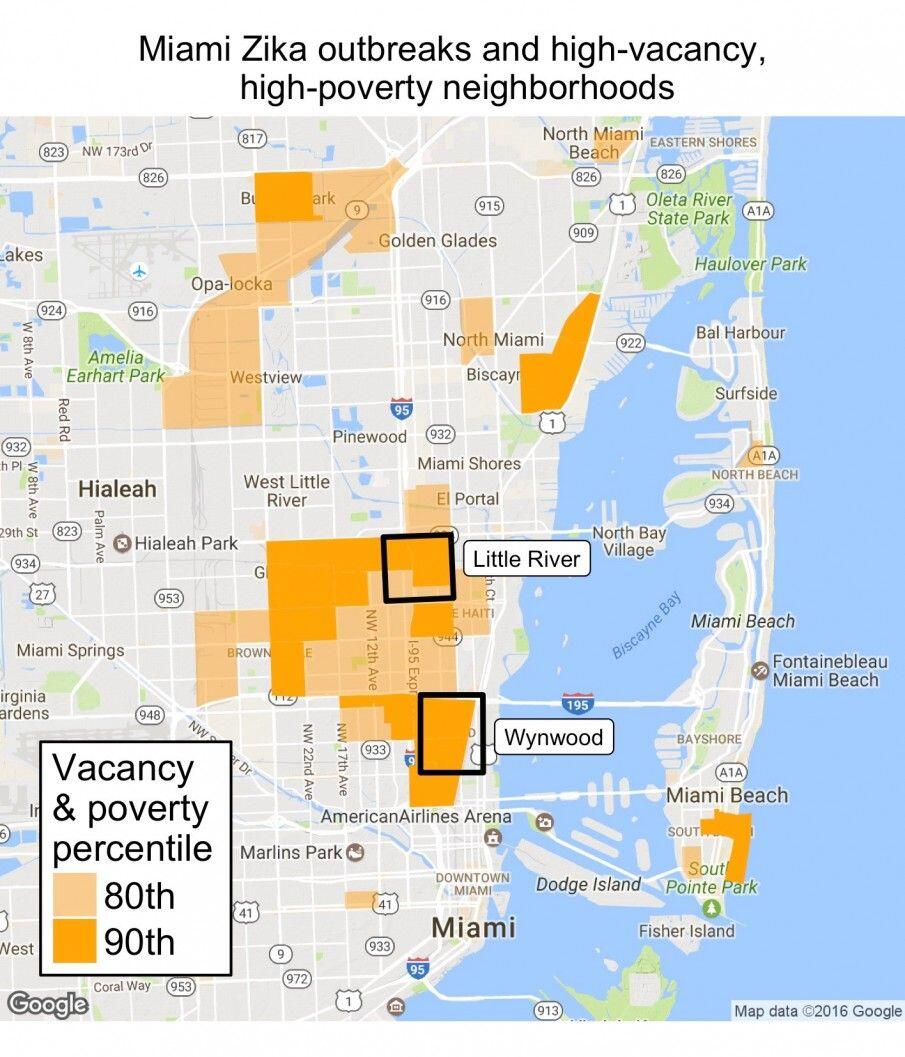

The extent of residential vacancy in Wynwood and Little River is remarkable. Out of Miami-Dade County’s 517 census tracts (geographical groupings of roughly 1,200-8,000 people), Wynwood and Little River’s tracts fall in the 95th percentile for proportion of addresses where no one is collecting mail.

South Wynwood has the worst vacancy rates in all of Miami-Dade County; Little River and North Wynwood both exceed the median vacancy rate by a factor of over four.

These connections make sense. When no one is using a property, it is a lot less likely to stay clean. That could mean more debris and standing water, where Aedes aegypti mosquitos like to breed. A study in urban Mexico, for example, found vacant lots were more than twice as likely to harbor Aedes aegypti as occupied properties: the mosquitos bred in water that had collected in used tires and other debris.

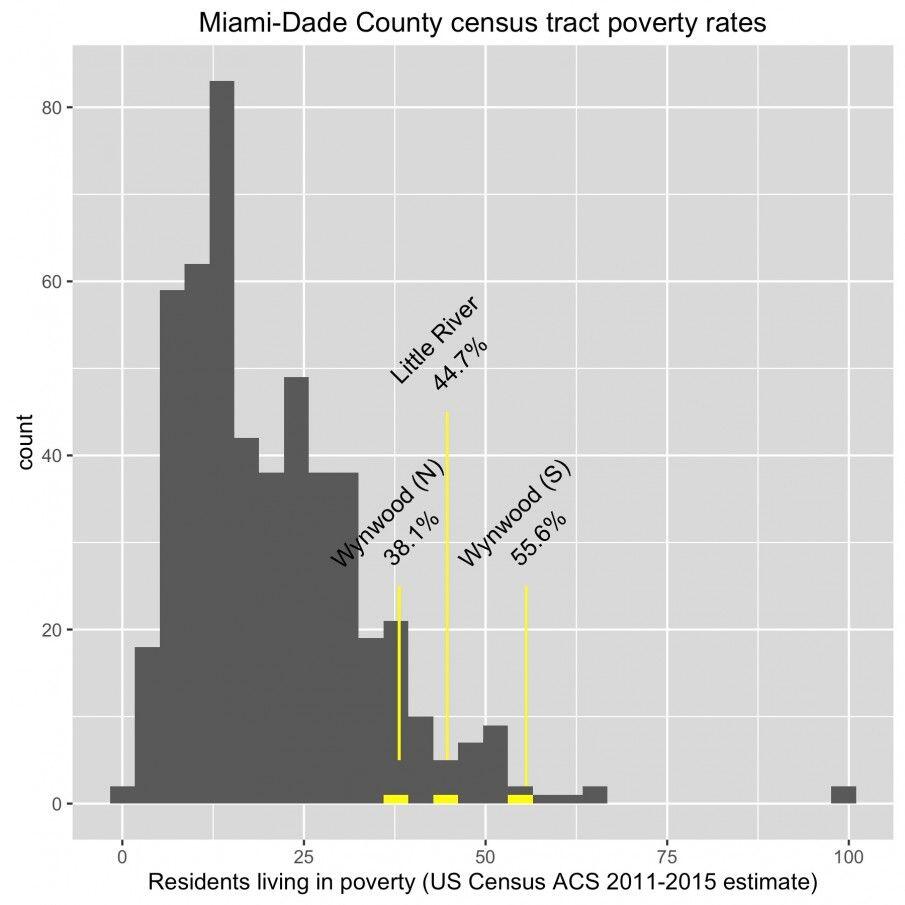

But these three Zika-affected tracts are not just remarkably empty; they are remarkably poor. According to the U.S. Census’s latest estimates, the median annual household income in Little River is just $20,873. In South Wynwood, it is $16,583. All three tracts approach or exceed the 40% threshold generally used to classify “extreme poverty.”

Poverty contributes to multiple potential Zika risk factors: inadequate housing conditions make good breeding sites; people might be less likely to have protective measures like window screens, air conditioning and mosquito repellent; they may be less able to avoid outdoor work and foot transit; and they may have lesser access to family planning and antenatal care services.

It has been argued that a Zika epidemic could be the next Hurricane Katrina with respect to its vastly disproportionate impact on poor communities of color. As of 2014, non-Hispanic Black was the largest racial category in South Wynwood and the majority in Little River. (The Zika transmission zone centered in Little River extended west of I-95 into Liberty City, the predominantly Black neighborhood where the film “Moonlight” is set.)

We might suspect poverty alone could explain these outbreaks. But poverty and residential vacancy aren’t strongly associated in Miami-Dade County: the correlation coefficient is only around 20%. In studies from other regions, poverty hasn’t emerged as a clear determinant of localized risk for Aedes-borne disease. For example, in urban Singapore, high-rise apartments were found to be less susceptible to dengue than housing compounds, even though the richest residents live in those compounds. And in Miami, the latest transmission zone missed the Liberty Square housing projects, instead finding the more sparsely-built environment of Little River, just a few blocks east.

Seeing these intersections between vacancy and poverty could prove predictive. Among Miami-Dade tracts, the Wynwood and Little River neighborhoods all score in the 90th percentile for both residential vacancy and population in poverty. They are clusters we could have picked off a map before the outbreak.

Knowing where to look

These patterns don’t prove that vacancy and poverty are perfect predictors of Zika. But for city governments looking to strengthen their safeguards against local outbreaks, these neighborhoods could be the place to start.

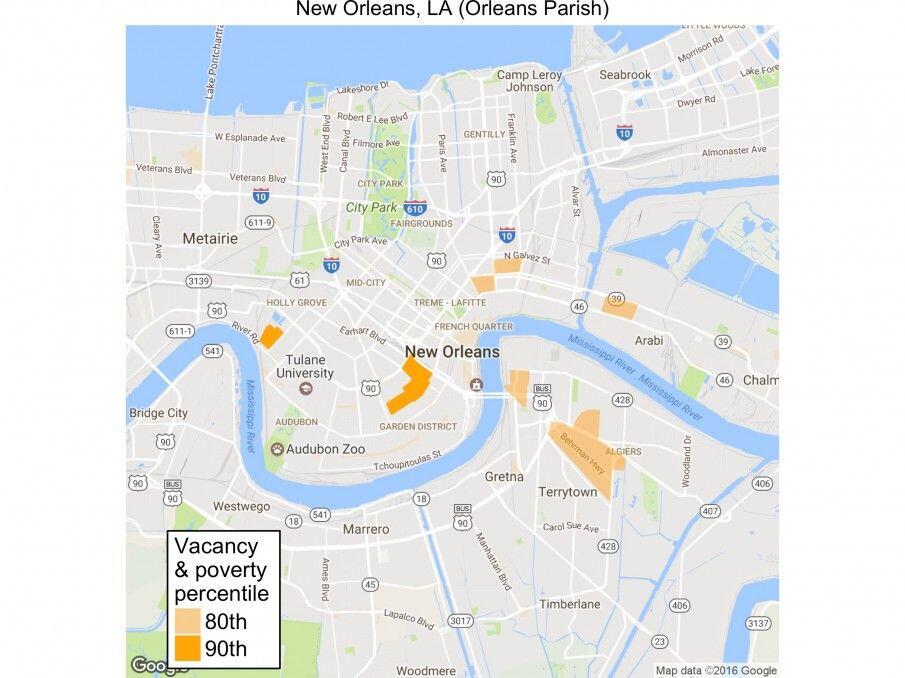

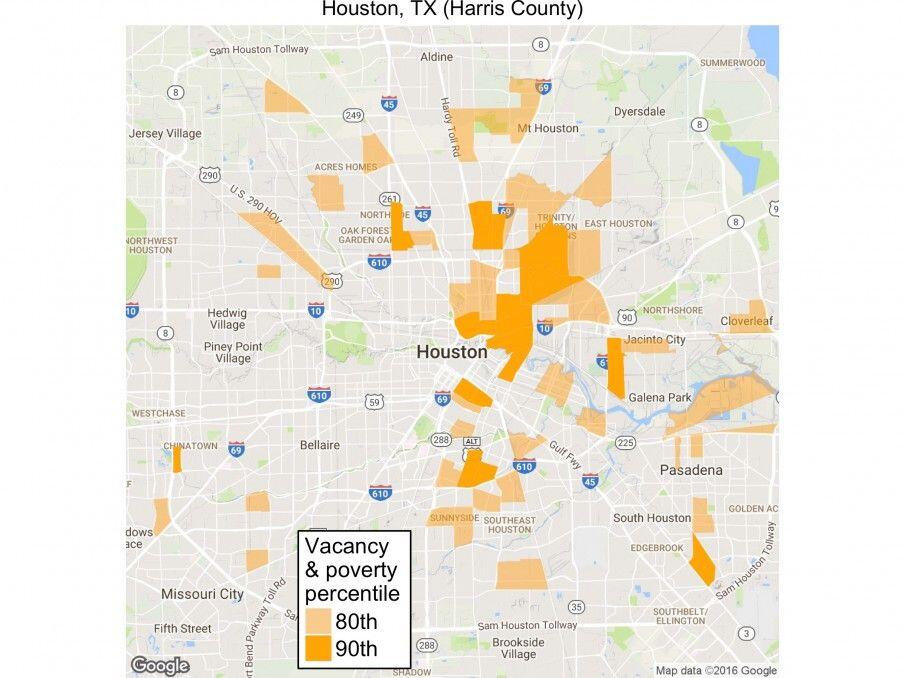

I plotted the same maps—showing neighborhoods that are outliers for vacancy and poverty, compared to the rest of their county—for New Orleans, LA and Houston, TX.

These maps show how big cities can differ. In Houston, vacancy and poverty are more highly correlated than in Miami or New Orleans. That means a larger proportion of neighborhoods exhibit high co-occurrence. Still, in all three cities we see concentrated co-occurrence in pockets near the city center. These areas—the low-rise inner city of Matthew Desmond’s Evicted—require higher-quality, affordable housing and better city services.

What cities can do

To tackle a problem like this one, no single government agency holds all the necessary data and authorization. Getting the right people and information to the table is step one. An interagency “task force” approach has played a role in successful efforts to reduce vacancy in South Bend, IN and to reduce crime in Boston, MA. Improved data access can fuel these efforts and is feasible in smaller cities as well.

Breaking down institutional siloes is especially salient in Zika prevention. While mosquito control activities are often led by county agencies, city agencies have information and authority that’s central to identifying and addressing vacant properties. For example, water department shut-off data can flag properties relatively early in their abandonment. Housing code inspectors, in many cities, can be authorized to enter premises to address public nuisances, including pests (often explicitly including mosquitos). Even the simplest solution — contacting a property owner to clear up the problem herself — might depend on finding a current name and phone number contained only in one agency’s records.

Long-term dividends

For cities already focused on vacant properties, Zika prevention can build on existing efforts. New Orleans, for example, has already built momentum on blight remediation, using data science tools to prioritize targets and behavioral nudges to increase homeowner action. Many of the right people and data, therefore, are already in place.

For other cities, the urgent task of Zika prevention could mobilize new interagency action on vacant properties. Whether those cities experience Zika outbreaks or not, they could increase housing availability and improve neighborhood conditions for years to come.

Top photo credit Monaghan et al 2016