What will the American dream house look like in the year 2100? Beyond the open plan kitchen and spare bathroom, a key selling point is going to be distance from coastal flooding. According to a

new study on climate migration, “13.1 million people in the United States alone would be living on land that will be considered flooded with a sea level rise (SLR) of six feet” by 2100. This is more than

four times the amount of people who fled the Midwest during the Dust Bowl, which is the largest migration in American history.

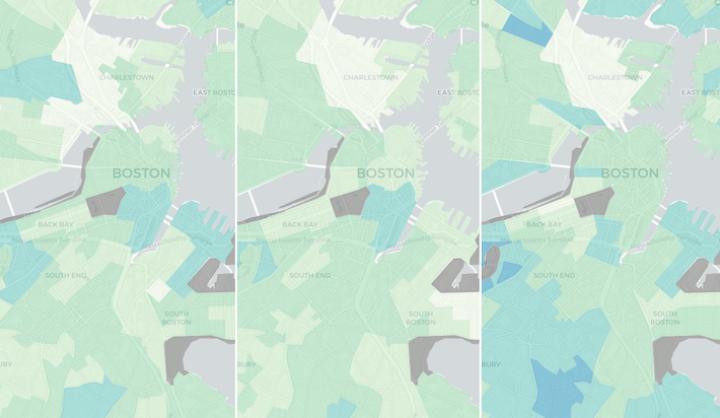

There are two reasons that policymakers and local governments should pay attention to these particular maps. The study authors, Caleb Robinson, Bistra Dilkina, and Juan Moreno-Cruz, used an original framework to model not only the directly affected areas, but also map the extended areas that are indirectly affected by rising sea levels. They also accounted for the fact that “the patterns of climate migrants will not necessarily follow patterns observed in historical migration data,” which other models relied on.

For example, the research finds that the Midwest will have “large indirect effects,” despite having fewer climate migrants than counties that are closer to the coast. This is because the Midwest currently has smaller populations and less migration than larger, coastal-adjacent cities, so the influx of climate migrants will weigh more heavily in those areas. Additionally, there will be flows of migrants between “pairs of counties for which there are no historical flows” since many people will want to stay in the same relative area, but be forced out of the most coastal county by SLR.

Also, people who would currently be considering moving to places like Miami or Los Angeles will be more likely to choose the surrounding, safer cities. If the preferred destination is flooded, those people are likely to move to the general area but choose somewhere just past the flood danger zone, which will in turn burden those areas as the coastal cities are hollowed out.

An influx of climate migrants will affect school capacity, infrastructure, housing/rental costs, transportation, and employment. This is already happening in places like Flagstaff, AZ and Chico, CA. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting the real estate market; more people are moving out of cities, housing prices have significantly increased, and there is new housing insecurity. Climate migration must be incorporated into current planning and policy, with particular attention paid to the risks of climate gentrification.

Utilizing maps like this one, governments can get a head start on the changes that are predicted to affect the youngest generation living in their cities right now. These children will likely be escaping SLR or accepting climate migrants, and they will need to inherit policies and plans that start addressing this coming reality right now.