Despite incredible strides in the last several decades to make America a more equal place to live, people of color still

face structural racism in nearly every part of their lives. The Aspen Institute’s Roundtable on Community Change defines structural racism as “a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity.” These significant economic and societal barriers that have persisted for centuries have cyclical and generational impacts that make it more difficult for people of color to climb out of poverty and improve their quality of life.

As the 2020 Democratic debates heat up, several candidates are proposing reforms that aim to address systemic injustices that continue to hurt Americans of color. Some examples of these proposals include granting voting rights to formerly incarcerated people, bringing an end to the cash bail system, making universal childcare accessible to all, and issuing reparations to descendants of former slaves. If implemented, it is possible that many of these proposals can help chip away at structural racism, but one major issue in particular has plagued American families of color that have made it near impossible to improve their economic standing: homeownership (or lack thereof).

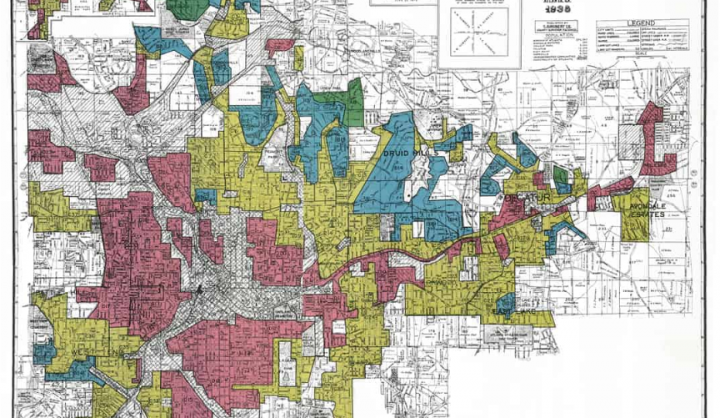

A few presidential candidates currently participating in the primary race including Senators Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris have recently brought attention to this issue through policy proposals that aim to make homeownership possible for disadvantaged families and people of color. The root of this issue dates back to the 1930s when the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) used housing conditions and racial, as well as immigration characteristics, of neighborhoods to classify mortgage risk. HOLC would “redline” neighborhoods where the population was majority black, minority, or immigrant to ensure those families would not receive financing to purchase or improve their homes.

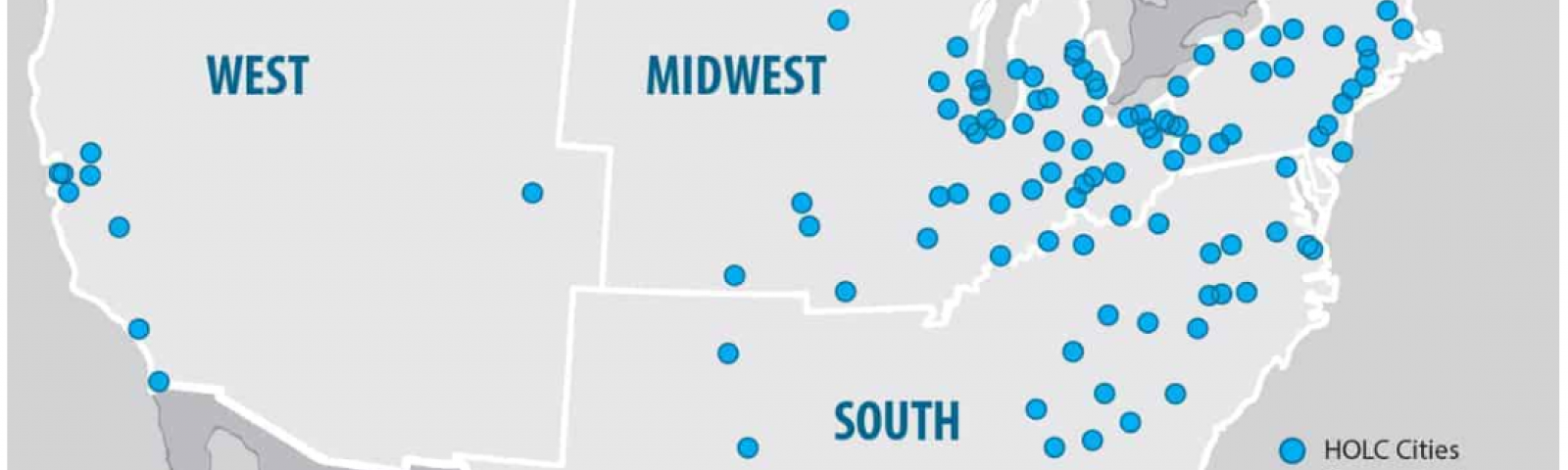

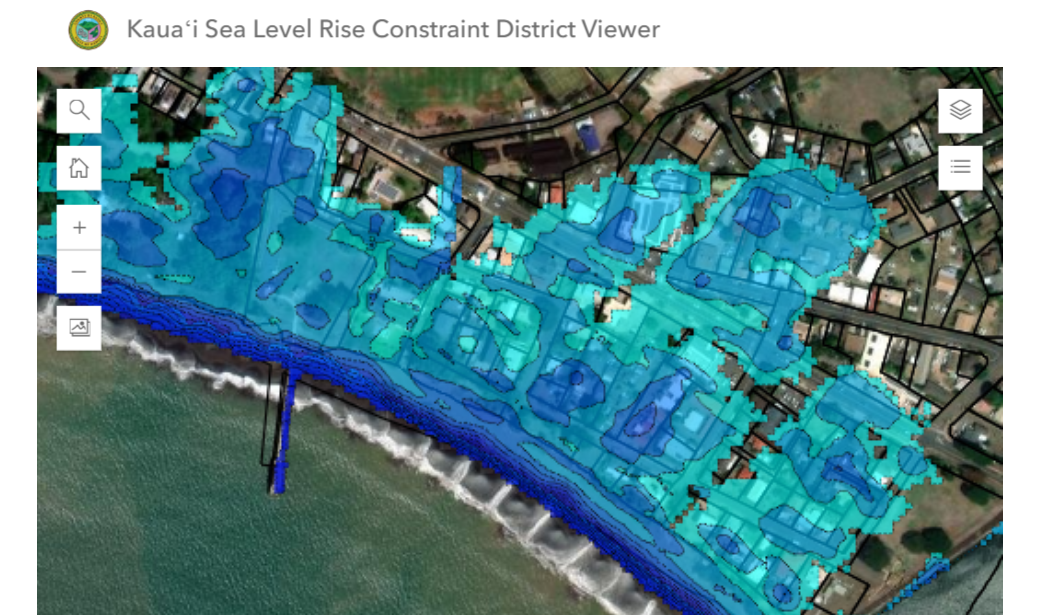

Redlining was banned in 1968 following the passage of the Fair Housing Act; however, the practice has had a lasting effect and is largely responsible for the levels of housing inequality the country is currently experiencing. To demonstrate just how much HOLC redlining has influenced the demographic makeup of America’s neighborhoods, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) in Washington, D.C. mapped the current state of the US’s formerly redlined neighborhoods highlighting lasting impacts. The study explored 114 different metropolitan areas across the country to compare HOLC maps from the 1930s to the socio-economic makeup of those same communities today.

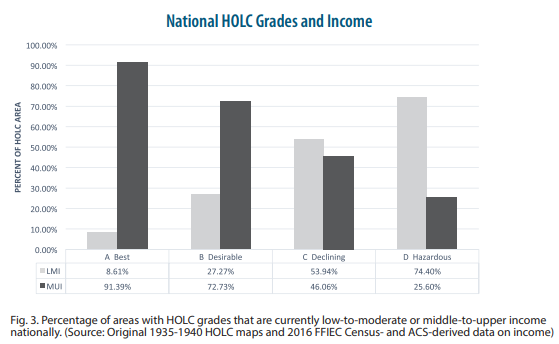

Among the key findings from the study (the official report can be found here), the NCRC found that 74 percent of neighborhoods in the study that were graded “hazardous”, and 54 percent of neighborhoods graded “Declining” by HOLC in the 1930s are low-to-moderate (LMI) income today. On the flip side of that, almost 92 percent of HOLC graded “Best” neighborhoods, and 73 percent of “Desirable” neighborhoods are Moderate-to-Upper Income (MUI) today.

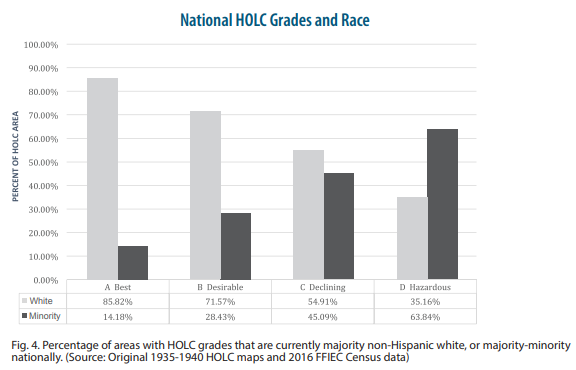

At the same time, 64 percent of HOLC-graded hazardous neighborhoods, and 55 percent of “Declining” neighborhoods are majority-minority today. Alternatively, 91 percent of HOLC-graded “Best” neighborhoods and 73 percent of “Desirable” neighborhoods are still majority white.

The study also showed that that there is greater economic inequality in cities where HOLC-graded hazardous neighborhoods are majority-minority now, suggesting that the less change there has been in demographic makeup of these communities over the last 80 years, the more inequality there currently is. The maps even showed that the neighborhoods that today are majority-minority after being redlined by HOLC in the 1930s are also associated with “hyper-segregation” where black and Hispanic residents are “unevenly distributed and have lower levels of interaction with non-Hispanic whites.”

Reversing the damage done by HOLC in the 1930s requires drastic change to even begin to move the needle in creating more equal cities. These maps provide a solid foundation for truly understanding the root cause of housing inequality, as well as the depth and breadth of the problem today. As city leaders works to address the effects of redlining, maps like these can help them better understand the environmental and socioeconomic factors determining the success or failure of their policies and make adjustments as these factors change over time.