- December 11, 2020

- COVID-19

Centralizing GIS Resources in State Operations

Under the leadership of former Governor Martin O’Malley in 2009, Maryland sought to change how the state operated. O’Malley restructured large parts of the government in order to centralize the state’s GIS resources and enable data-driven governance, a legacy that has been carried on by Governor Larry Hogan.

To centralize GIS, state leadership pulled GIS leaders from various state agencies including economic development, environmental protection, emergency management, public health, education, housing, and others to serve under the new Geographic Information Officer (GIO). The GIO’s office, now led by Julia Fischer, is made up of seven full-time GIS subject matter experts who are positioned by area of specialty (i.e., emergency management, housing, etc.) and are assigned geographically to different regions of the state. The team is in place to serve two purposes: first, to serve as a state-level liaison to coordinate data and information sharing between state and local agencies, and second, to enable the hundreds of GIS users embedded within government agencies statewide to apply GIS best practices in operations.

Fischer’s team is housed within the Maryland Department of Information Technology (DoIT) and reports to the Chief Information Officer. Fischer’s team is tasked with managing the state’s entire enterprise GIS platform which is known as “MD iMAP.” In FY 2020, the GIO’s office moved to a fully reimbursable chargeback format which requires state agencies to pay the GIO’s office to maintain mapping and data resources. This model facilitates collaboration with other state agencies to fund the maintenance of MD iMAP and all services supported through the platform. These services include open data, maintenance of hundreds of mapping applications, and the state’s Software as a Service and desktop GIS platforms. This model allows the team to serve sister agencies while also supporting local, regional and county agencies in need of GIS resources and support.

According to Fischer, “we maintain the foundation so that everyone else can do the fun stuff.” Her team works to ensure GIS users statewide are able to do their critical work with whatever licenses they need and to help with troubleshooting assistance or application development. “Our focus is to do all of the heavy lifting required to support GIS users so that these agencies can focus on applying it in practice,” she continued.

Beyond backend system maintenance, the team has also played a crucial role in fostering and sustaining trusting relationships between all levels of government. They’ve done so by serving as a reliable resource to go to whenever needed and coordinating between agencies that are working to solve similar problems.

GIS Office Positioning Enables Data-Driven Pandemic Response

This strong GIS foundation ultimately served Governor Hogan and the state well during the COVID-19 pandemic. Long before the pandemic hit, a public health data and information sharing pipeline had already been built between county public health departments and the state as part of the restructuring effort. This allowed the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) and the counties to quickly shift their focus to support rapid information sharing for COVID-19 response.

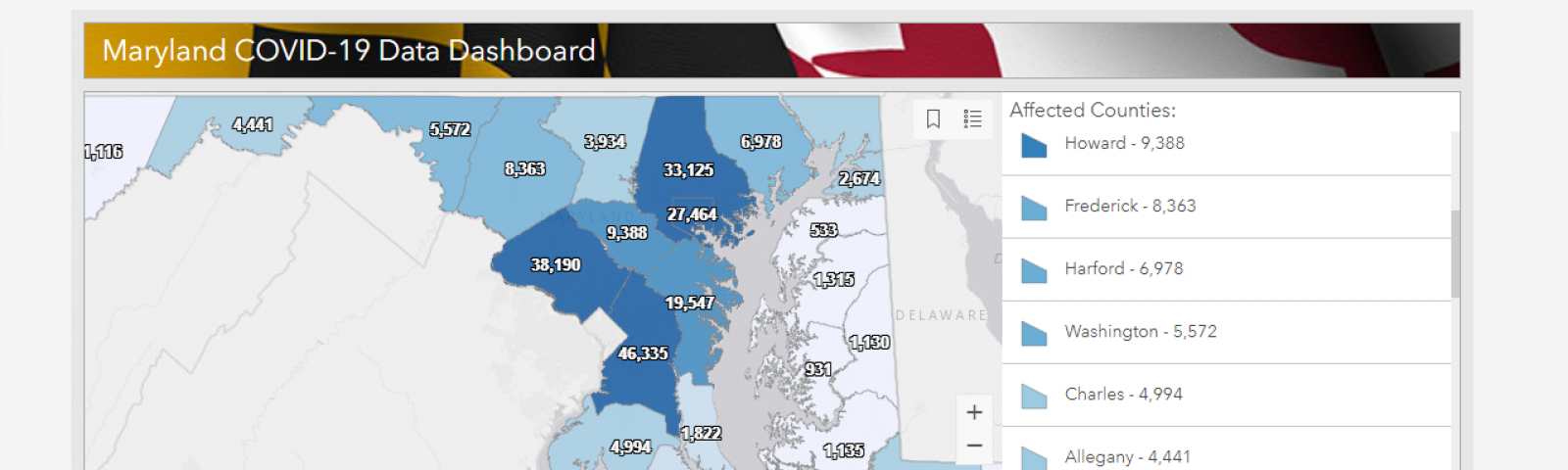

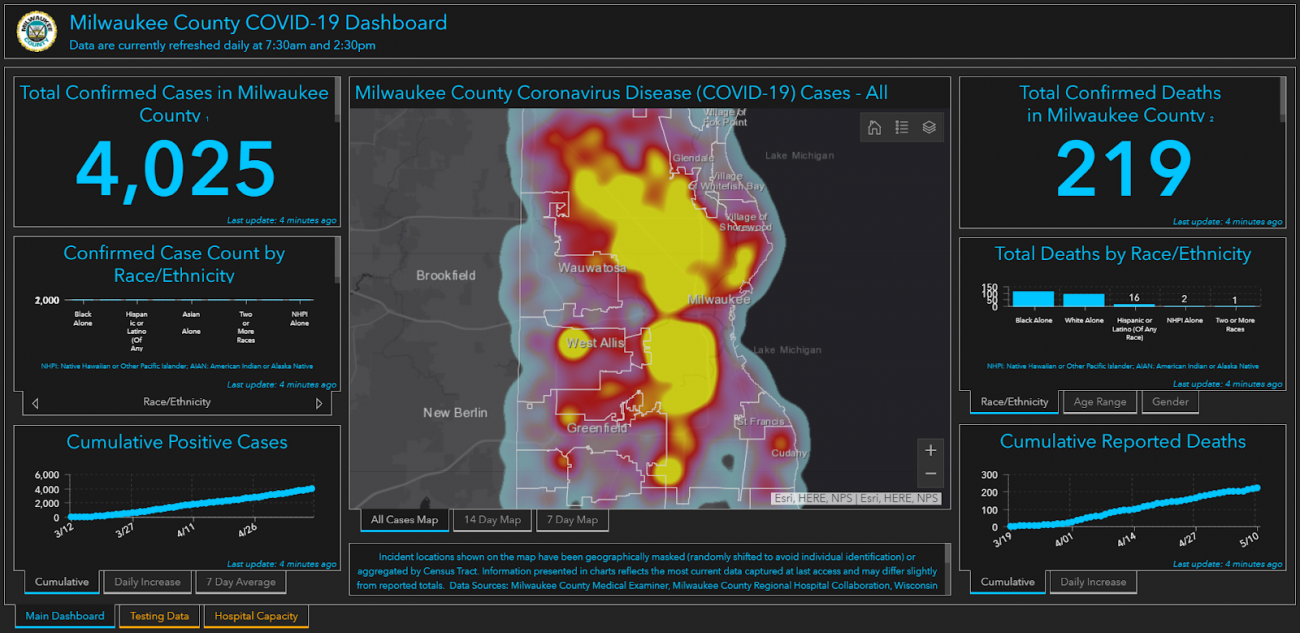

Early on, Fischer’s team knew they would have to work quickly to ensure timely and accessible information sharing with the public, as well as with state leaders in other agencies. Her team was able to quickly launch a COVID-19 hub site which brought together critical public health and government resources as well as communications on one site. Thanks to the preexisting relationship and data flows between county health departments and the state, her team was able to create the state’s dashboard showing where positive cases were spreading or emerging using data directly from county health departments. From there, GIS was thrust into the spotlight as a primary tool being used in Maryland’s fight against the virus.

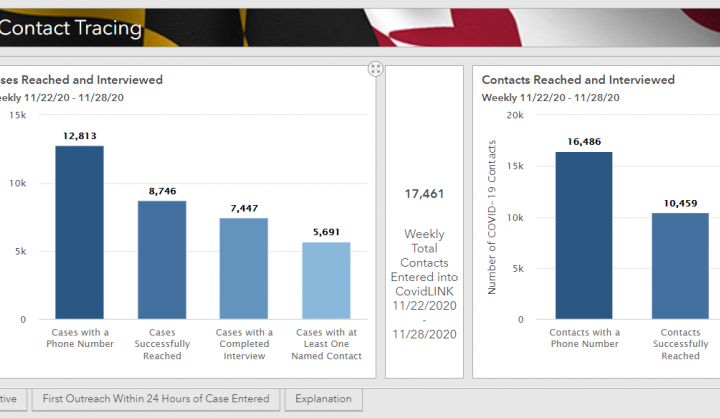

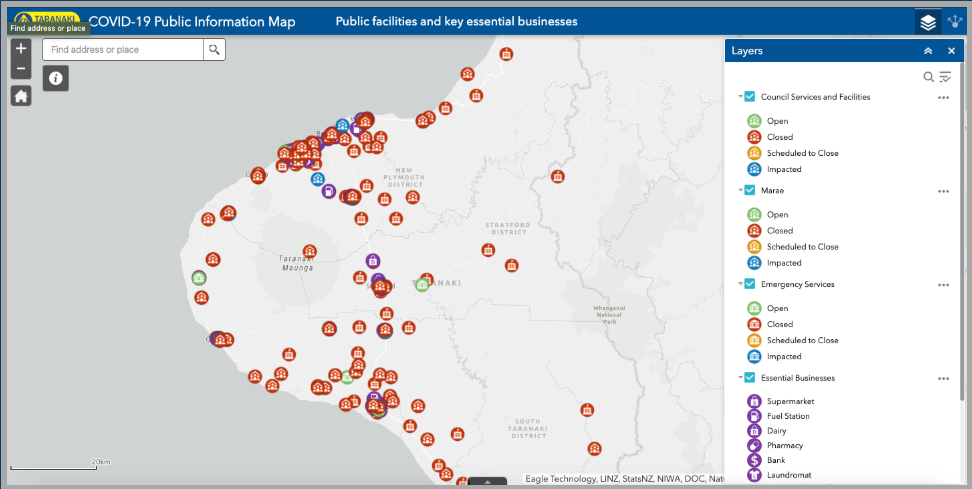

Today there are various maps and dashboards on the public-facing site in addition to the COVID map, including a testing site locator, charts displaying anonymized contact tracing data (see below), as well as dashboards highlighting cases and trends in nursing homes and schools. Fischer’s team monitors the site 24/7 and is constantly adding new metrics and data layers based on feedback from state government leaders, elected officials, and the general public. The team currently has over 40 open data layers available on the site, which is updated on a daily and/or weekly basis depending on the type and category of data. Her team works tirelessly to ensure that the data is well documented and descriptive so that decision makers from the government level down to individual families can make informed decisions using the information presented.

In addition to building public-facing maps and dashboards, Fischer’s team has worked closely with MDH, the Maryland Emergency Management Agency, and the Governor’s Office to build internal-facing operational dashboards for response and recovery efforts. For example, the team is working closely with the communications team at MDH to determine where to target public health interventions such as messaging and education campaigns. They are also working to ensure more strategic placement of COVID-19 testing sites based on the location of existing outbreaks and are also creating an early detection dashboard to anticipate where new outbreaks may emerge. They’ve also built a personal protective equipment (PPE) tracker that monitors the location of PPE throughout the supply chain including where it is purchased, where it is being distributed, and what the supply levels are in different areas of the state.

Today, the team is in the early stages of building location intelligence capabilities into the state’s contact tracing system. This will allow contact tracers to plot not only where existing cases currently are and where they have been, but also to connect positive cases back to the physical locations where outbreaks may have originated or where they are emerging. This helps tracers see visually where cases are spreading and to connect cases that were previously unrelated back to the locations where transmission may have occurred. “We are working to map as many of the locations and data points as possible within the bounds health care data privacy laws allow,” said Fischer. While this data will only be viewable to a small handful of people in state government, the team is taking a careful, measured approach to ensure the integrity and security of the data entering the system before scaling these capabilities.

Fischer and her team have demonstrated that having advanced GIS capabilities is only part of the equation. Where the technology is positioned and how it is operationalized are equally, if not more, important. In Maryland, GIS is the foundation upon which state and local leaders collaborate and make decisions. The way the state structured and embedded its GIS resources enabled it to rapidly share and communicate critical data, operate from a single authoritative data source, and to collaborate across agencies and at different levels of government. This positioning also helped the state shift rapidly to support a range of COVID response and recovery related efforts at a pace unmatched by many other states in the US. It also doesn't hurt that Maryland’s health department is one of the top ranked in the nation for public health emergency preparedness.

With these advanced data-driven and public health capabilities, it is no wonder public health leaders such as Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Eric Toner of Johns Hopkins University praised Maryland for its response to the virus. Today, Maryland continues to serve as a model for COVID-19 response that other states would be well-served to replicate.