- October 2, 2019

- Civic Engagement

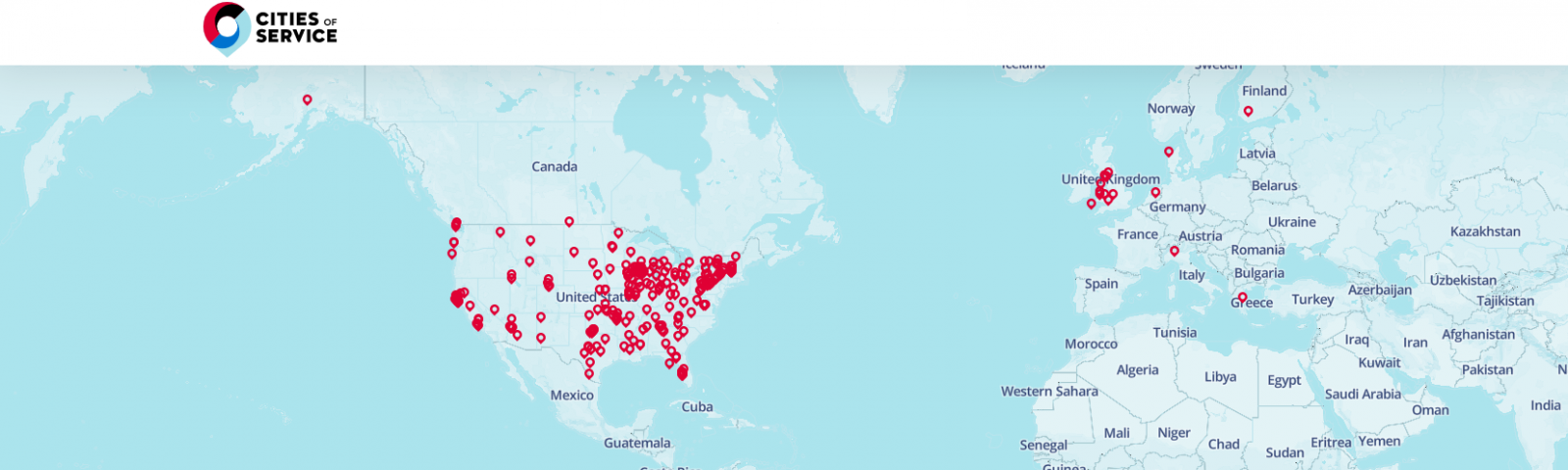

Myung Lee is a staunch advocate for good customer service. If you go to her Twitter account (@myunglee), she says you’ll see Tweets about women, children, and cities—but you’ll also see her bristle at FedEx and Delta, proselytizing about quality customer service. It all relates to Lee’s work as the Executive Director of Cities of Service, a nonprofit organization that helps mayors build stronger cities by modifying the way local government and citizens work together. The organization, based in New York City, supports a coalition of more than 270 cities, representing over 73 million people across the Americas and Europe.

Customer service is important when it comes to helping cities design programs for their residents, Lee says, because city governments need to know who their consumer is and how to engage with them. And that comes from engaging with residents about what they want to see in their cities. If engagement is not done well, then … mishaps occur. Lee expands on this in our conversation below about effective citizen engagement models. We also discuss how her own city government experience gives her insight to her current job, the organization’s Love Your Block AmeriCorps VISTA Program, and how important citizen engagement is to democracy. Read more to learn how you too can improve democracy through citizen engagement!

Stefanie Le: What makes you so passionate about citizen engagement and the work that Cities of Service does?

Myung Lee: I am a big believer in democracy and I’m a big believer in local governments. The work that I do everyday at Cities of Service allows us to bring people together who are essential to democracy and cities—the people who live there and the elected officials who represent them. Doing citizen engagement well means that they are able to build better cities that are grounded in trust and relationships. With that, I think cities can get anything done. I feel like we are the luckiest people on the planet to be able to do that work.

SL: How has your experience as a Deputy Commissioner with the City of New York Administration for Children’s Services (2012-2014) translated into your work with Cities of Service?

ML: It’s given me a greater understanding of what happens inside city government—not just in mayors’ offices but also at the agencies where a lot of the work gets done. It’s given me greater insight into what it’s like to be a city employee that’s toiling away in city government agencies, and a greater understanding as to why city employees may be reluctant to go out and engage community members and what gets into the mindset. It’s given me empathy which allows me to do my work better and allows us to better understand where everybody is coming from. My experiences within and outside city government, not just as an individual, a voter, and a citizen in a community, but also as a nonprofit leader, a business leader, and a city employee has given me an all-around exposure to better understand what everybody is coming to the table with.

I think it’s hard for city employees who don’t often control the politics of the matter. There are a lot of reasons that go into why community members get angry—and it may not be the fault of the individual staff member at a city agency why certain policy decisions were made. This is part of why we really believe that city leadership—the mayors, the city managers, etcetera—all have to be on board with wanting to do more citizen engagement because the frontline staff are getting yelled at. Time and time again, the city employees may be facing citizens and community members who are angry because of decisions that have been made about their lives, about things that impact them without having been given the opportunity to understand, engage, and voice their opinions or share their experiences. As a result, the frontline staff bears the brunt of that built up tension and anger, and I understand that.

SL: Based off of what you just said, how would you improve the process between residents and city staffers?

ML: Not everybody is going to be happy all the time with what city government decides. Governing means that you can’t please everybody because you’re governing for an entire city, and for a city as large as New York where there’s 8 million+ people, it’s impossible to make everybody happy. Having said that, I believe it would be better if the leadership of the agency, city government or whoever is the decision-maker of the policy are able to empower the staff who are citizens as well. It’s best to empower the staff who are on the frontlines to engage community members and citizens from the get-go, so they’re not just the deliverers of the decisions that have been made, but they are involved in the fact-gathering process and in talking to the community residents about what may be coming, what are their opinions about it, and the realities and experiences on the ground. Getting the staff involved and allowing them to build relationships, as opposed to just being deliverers of news, I think would be helpful.

SL: Can you tell me about the citizen engagement model that Cities of Service utilizes?

ML: Our model is grounded on the relationship between local government and its citizens. If you have a relationship, then it’s going to give you trust. We believe the way city governments get to that relationship is by having the leadership involved, because governments need to be able to have the decision-makers behind the efforts. With the leadership involved, they may decide from their perspective what is best for the city’s population with the 8 million people in the city overall. Or they may decide in this particular community—from where one sits as the mayor—this is what they think is necessary in that particular community. Cities then need to have the city officials go out and deliberate with the community members in that particular area to confirm and affirm.

Cities need to ask: are we right in assuming this is an issue? Are we right in assuming that blight is an issue in this particular area? Are you experiencing that as a problem? What about it is a particular challenge? What about it is the thing that’s keeping this neighborhood in this particular situation, versus being able to blossom and grow and develop? Having that deliberation and doing it right means that city officials are actually really listening, and not just sharing a decision that’s already been made. That process of deliberation is something we believe is really important. And then, once city officials get to a place where they’ve listened, they’ve talked, they’ve heard from residents, they’ve exchanged ideas and information—they can collaborate together on what a solution may look like and what each party can bring to the table to actually implement that solution.

We really believe that it’s important to have people contribute something to the solution, even if it’s just their ideas and their experiences, because everybody has something to offer. It’s not like a vending machine where a citizen pays a certain amount of taxes or votes and the government now has to deliver—it’s about partnership and it’s about working together. You collaborate together and then celebrate the results. And the result could be that is was a mess! The idea is that maybe what you had together didn’t work out, but at least everyone is in it together, so things can be tweaked along the way. And hopefully there is a solution that’s positive at the end. By having deliberation, collaboration, and results—that leads to a relationship.

We recommend that city collaborations start with small things at first, because the idea is to start with a foundation upon which cities and their residents can continue to build on. We’re hoping that by doing small things, building on them, and doing rinse and repeat over and over, then they can actually build a relationship with the community members. Those relationships will then allow city officials to go to residents with tough things. Even though they may not agree with city officials on particular issues, residents know and trust that the city is coming from the right place because they have worked side by side with city officials on other things, and that can lead them to see that the city truly has their best interests at heart.

And that goes both ways—oftentimes city governments don’t necessarily trust the people. And because they don’t trust them enough to be transparent, they don’t trust them enough to be sharing information with them. By working side by side and building that relationship, they’re able to build trust on both sides. So when the advocates and the community members come to the city government and say, “Hey, this is really a bad decision that you made,” city government officials could actually sit and listen. Versus saying “Oh, they’re just complaining because they don’t like something.” City officials may actually trust residents enough to listen to what may be a problem. That’s our model.

SL: What is the Love Your Block AmeriCorps VISTA program?

ML: Love Your Block is a program that’s been with us since the beginning of the creation of Cities of Service. It’s a really great program—partly because it’s so simple. It allows the city to give out small micro-grants to community organizations. It is going as micro as you can—to the block associations, a nonprofit organization, or an informal group. Cities of Service will identify an issue—it could be about resilience and sustainability, food access or neighborhood blight, whatever the situation may be. And the city will say to the community, “Hey, we think this is a problem and we think that there’s many houses in this area that are going into blighted situations, getting a lot of housing code violations and it’s going to soon lead to tax levies and potentially people being evicted. So we want to figure out how to solve this problem and we think that because you live there, you’re the best ones to come up with the solution and we want to hear from you.”

So then communities members will organize, and they will apply to the city for a grant. Depending on need, the grants range from $250 or smaller up to $5,000. In some cities if they’re better resourced and have bigger problems to deal with, they’re going to up $10,000. It’s generally in the range of $500 to $2,500 and the program will make the funds available. The city will also bring in other resources like picking up the trash or making certain, bigger tools available for the residents to use; and then the citizens will propose solutions for what they want to do. In the current round, we have ten cities that are legacy cities (cities that have lost big industry) and they’re focused on things like housing code violations. The grant premise is: neighbors will come together and fix up the exteriors of neighborhood homes that really need the help, before they get into code violations. Or before they are in code violations but can’t afford to pay the fines. The community says to the city, “We need money for paint, we need money for paintbrushes, and we need you to come and collect all the weeds and trash that we get out of their yard.” And the city says, “Great!” And once their application has been approved, they come together, bring in the volunteers and the city will support with either helping them to recruit the volunteers or just giving them cash and they’ll go ahead and fix that.

The benefit to the Love Your Block Program is that it is creating social cohesion between the neighbors—you’re actually getting to know who lives next door, you’re getting to help the people that are in your neighborhood, you’re getting to know how you can be effective and empower community members. Working together strengthens the social cohesion. At the same time, it’s also giving those neighborhood groups social capital, because now they know that by coming together they have access to city resources. And now they have this movement, where they can say to their neighbors, “We have done this and we know that together we can do the next thing.” We think that the power of Love Your Block comes from strengthening social cohesion and increasing social capital, especially in communities that have traditionally been disempowered.

SL: In your words, how would you say citizen engagement influences or affects democracy?

ML: It’s about helping to build relationships and building trust in people and in government. There’s so much going on now with social media—people are doing more and more with direct mobilization rather than relying on representative government.

For example, in places like Hong Kong, citizens were actually able to affect change by mobilizing and protesting. And Amazon pulling out of New York when citizens railed against it. Those are examples of how direct mobilization worked to affect change. Now, I don’t necessarily think that’s an effective way to govern a city or a state or a country—it is very disruptive. There’s also danger when you have that kind of direct mobilization politics that the minority voices aren’t going to be heard. So there’s a reason why our country was founded on a representative government model. Of course, it’s not working perfectly right now. There are a lot of things that are messed up. But I think that we can do effective citizen engagement at the local level, and help to build that trust in representative government.

It is allowing one to build trust in the people and the government and building the relationships so it will be less likely to head down the path of mob rule. Sometimes mob rule is good, and we all need to stand up and resist but at the same time, but it depends on which side of the fence you’re sitting on. I think that effective engagement at the local level—and it’s easier at the local level because you see them every day—will help to build trust and strengthen our democracy.

SL: What would be your top three tips for increasing citizen engagement or doing citizen engagement effectively?

ML: The first thing is it takes time, which is sometimes a challenge for elected officials because they’re not there forever. But this takes time because it has to be an authentic and honest relationship. And that’s my second thing—you have to build the social infrastructure to actually be able to engage the community. If your community is filled with transient residents and there is no scaffolding to build upon, you need to take the time to build that somehow. You need to either put in infrastructure for the nonprofits to grow or something in the community that will be able to continue on with the engagement from the community side, as well as infrastructure within city government that will allow cities to engage with the community members. There has to be that investment of time and resources to really make this work.

Additionally, you have to be authentic and honest about it. For example, when we get phone calls from city governments that are interested in doing citizen engagement, one of the first things we ask is: Why are you interested in doing this? What’s your end goal? And if it’s just that they say, “Well, we want to do this thing and we want to make sure that the citizens are on board with us.” Then we say, that’s not engagement, that’s information. You have to know the difference between the two, and you have to be willing to listen. You have to be willing to solve the problem together, and you have to be open to the process, even to a point where you may have to change what you designed. It’s better to do it early and to take the time to do it right.

SL: What are the most common issues or obstacles you see with cities struggling to achieve effective citizen engagement?

ML: From the city side: they want things done quickly, and they want to just communicate information. Engagement is not a PR campaign—you need to have effective communications as a part of the strategy, but it can’t be the end goal. Looking at both the city and the community, a lot of the times it’s that the community doesn’t have a social infrastructure. I mentioned transient populations (cities that have renters as the predominant population); it’s hard because they’re not there for the long term and they’re not as invested. So how do you get those folks invested? What do you do? Some of the answer may be that you don’t get those people invested, but you build a social infrastructure. Therefore, cities have to build in a nonprofit infrastructure or something similar on the ground so they have people that are there for the long term that care about that community even if the people that live there may be going in and out. Then cities can start to grab a few—even if it’s 10-20% of the transient population—you’re at least grabbing some of them, but somebody’s on the ground to do it.

SL: Do you have any examples of a government successfully utilizing and encouraging citizen engagement?

ML: Recently we were talking to city government officials in San Francisco, as they’re one of our finalists for the Engaged Cities Award. San Francisco, if you think about it, is a city of a lot of people who are working in the tech industry who may or may not care about what city government is doing. And a lot of the time, they feel vilified because there is a negative narrative of “these tech billionaires.” What San Francisco has done really well, though, is reach out and engage employees of those companies to help the city solve big problems. They’ve gotten individual employees of Google and other companies to really understand what governing looks like and how problem solving happens in city government. They’ve also managed to get city employees to understand how to solve problems differently because they’re of the design thinking perspective that a tech company employee, private sector architecture firm, or consulting firm might have. By coming together to work on a problem, they start to see each others’ perspective. And I think that changing perspectives is something they’ve done really well.

One of the big problems that San Francisco identified recently is a problem with how citizens were applying for affordable housing. In order to apply, eligible individuals would have to apply with paper applications, wait in line, and see if they made the cut for the lottery every time a developer had some affordable units available. From there, they still had to fill out more paper applications to apply for the actual affordable housing unit and see if the developers would accept their applications. It was a long process, and it often took people out of their jobs to wait in long lines and fill out paper application after paper application to make this happen. The city department knew that that was not the most effective way to go about doing this, scoped out the problem, and reached out to its pool of companies that they were talking to. Google volunteered to help and they put together a team of folks who actually sat with city government for a month and really looked at how the process works or doesn’t work, and then went back to their offices and figured out a way to bring this process online. They also spoke to the developers who were really reticent to get involved because they thought it would be more work for them, and the Google volunteers were able to explain that actually doing this online would be less work for them. They talked to the residents about what their pain points were and then helped the city create a system and a tech platform for them. This essentially allowed residents to apply and find all the information they need online. The new platform enabled residents to hit a button every time a new developer comes online and they would get an email that said, “Hey, you may be eligible for A, B , C, or D developer.” Then the resident can go and check to see if they qualify. They’re informed online whether or not they won the lottery, and then whether or not they get the application. All so they don’t have to take time off from work, and they do the application once online. It’s simplified the process so much that now approximately 90 percent of the applications are done online.

When we spoke to the employees at Google and others who were involved, they kept saying over and over,“I now understand what city government does and I now understand how it impacts my community where I live. And this has given me such greater appreciation.” And they’ve all stayed in touch with city staff that they’ve worked with, and followed up with them when they find resources that might be helpful on other issues. So they continue to stay engaged and work on connecting with city staff, which I think is a real boon for both the city staff and the employees of these corporations.